Neuroscientists Unlock the Secrets of the Body, Breath, Mind Connection

The ancient wisdom traditions have long known the intimate connection between the body, breath, and mind. In yogic tradition, the practice of regulating breath, and thus the life force, is known as Pranayama.

While there are numerous pranayama practices that modify breathing patterns in various ways, a daily pranayama practice is said to have profound effects on physical well-being, relaxation, mindfulness, and eventually heightened states of awareness.

Today, western scientific research is steadily reaching the same insights through empirical studies that great masters discovered thousands of years ago through penetrating contemplation and inquiry into the nature of reality.

In his book Buddha’s Brain, neuroscientist and meditator Rick Hanson compiles the latest physiological research of modern psychology and neuroscience in relation to the brain, emotional, mental and physical states, and meditative practices. This article will exclusively draw from this research to explore the modern neuroscience behind the breath-body-mind connection and provide readers with a simple pranayama (breathing technique) to alter physical states in the body which increase relaxation and repair damage caused by chronic stress.

Understanding The Nervous System

Nerves are your body’s major communication pathways of information. The nervous system is the complete network of nerves throughout the body, starting from the brain, running through the spinal column, and radiating outward to the muscles, skin, and all the organs.

The brain is your body’s command center – receiving the latest information from all the nerves throughout the body, processing that information, and sending out commands to handle current conditions.

Consider accidentally touching a hot pot handle: the nerves in your hand relay the hot sensation up through the arm, through the spine, up to the brain. The brain processes that information, determines the heat is dangerous, and relays a message back through the nervous system to pull the hand away as quickly as possible, and all of this happens in a fraction of a second.

The 2 Parts of the Nervous System

The nervous system is composed of two parts:

1

The central nervous system, comprising the brain and spinal cord (command and processing center).

2

The peripheral nervous system, comprising all the other nerves that connect the central nervous system to the senses, organs, and muscles, allowing the body to receive stimuli and respond to its environment.

This peripheral nervous system is again divided into two parts. The somatic nervous system controls conscious action, like picking up a glass of water to drink. This system helps you to interact with the external world, avoiding dangers and approaching desires.

Alternately, the autonomic nervous system operates largely without conscious awareness, regulating breathing, metabolizing food to fuel activity, balancing hormones, maintaining the immune system, regulating all of the organs in the body without your conscious effort.

The unconscious autonomic nervous system can be subdivided once more into two systems that will predominantly shift our bodies into either stressful or relaxing states. These are the systems we will be investigating to see the physical and mental effects of mindful breathing or pranayama practices.

A Deeper Dive Inside the Autonomic Nervous System

The two systems operating below conscious awareness are the sympathetic nervous system (SNS), which regulates the “fight-or-flight” response and the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS), which regulates the “rest-and-digest” response.

These two systems, like a see-saw, hold a delicate balance of power such that when one system gets turned up, the other is turned down. When activated in a balanced way, the SNS fuels increased feelings of passion, excitement, enthusiasm, alertness and intense focus.

When your brain perceives danger or is stressed by current conditions, the SNS takes over, cascading commands throughout the body to prepare you to either fight through or flee from the stressful situation.

These commands include drawing energy away from digestive and reproductive processes and toward the muscles for sprinting or fighting, accelerating the heart rate and raising blood pressure, and releasing hormones like cortisol and epinephrine.

Epinephrine increases the ability to form lasting and strongly-impressed memories, but also increases perceived levels of fear.

Cortisol suppresses the immune system to decrease inflammation from wounds and it stimulates the amygdala in the brain, which is hardwired to focus on negative information and react intensely.

These physical effects drive people to respond to stress either with fear (“flight”) or anger (“fight”). These responses have been quite useful in surviving dangerous situations throughout our evolutionary past and forming vivid, negative memories to encourage avoiding future dangers.

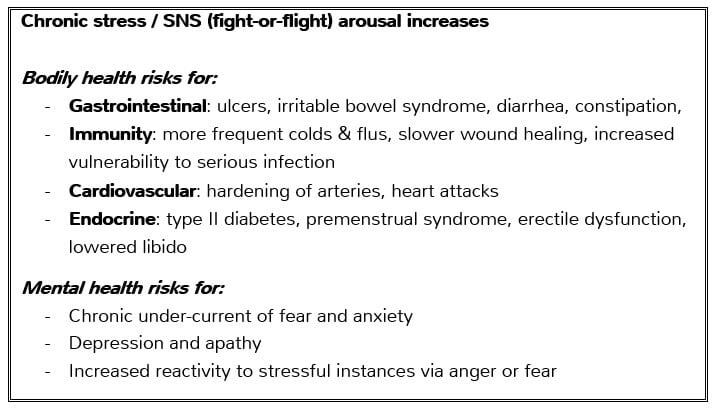

But, in the modern life, regular low-grade stresses lead to persistent over-activation of the SNS and this can manifest health problems in digestion, immunity, heart-health, hormonal and reproductive systems (see table), as well as increase susceptibility to chronic anxiety and depression.

Alternately, when at ease, the PNS (“rest-and-digest” system) takes command, drawing energy away from extremities toward the core of the body, repairing organs, digesting and assimilating nutrients, and regulating hormones.

On a mental level, the PNS is in charge of producing feelings of calm, relaxation, and contentment, but in excess leads to drowsiness, sleep, and lack of focus.

Consider a sigh…

This is the body’s natural and quick attempt to activate the PNS.

A frustration occurs, and the breath unconsciously and automatically shifts: a short deep inhale, followed by an extended exhale, with a constriction of the throat (similar to ujjayi pranayama).

Sighing gives an immediate push toward PNS dominance and instant softening of tension in the body.

Balance is the Key

Dominance of PNS with some SNS activation is the natural state. Just as yogis purport that the natural state is calm, peaceful and present, physiologists would agree, noting that PNS dominance is the natural, normal equilibrium. The SNS activation in small amounts helps increase focus and alertness, but when it dominates current conditions, drives the body out of balance and wellness.

Thus, the greatest long-term benefit is in bringing the two systems into balance and one practical way to do so, is through controlling the breath.

Along with an increased heart rate, SNS activation changes the breath, making it faster, more shallow, and with a greater emphasis on inhales to draw in more oxygen to fuel fighting or fleeing.

Conversely, PNS activation slows and deepens the breath, with more emphasis on exhales.

But, this relationship between the breath and nervous system is two-way: activation of the nervous system can change the breathing patterns, and the breathing patterns can change the activation of the nervous system.

With each inhale, the SNS gets slightly activated, encouraging the heart to beat a little faster. With each exhale, the PNS is stimulated, encouraging the heart rate to slow down slightly.

By extending either the inhale or the exhale to be slightly longer than the other, we will bring more activation into the SNS or PNS, respectively.

Practical Pranayama Practices

The following practices are designed to stimulate the PNS; thereby reducing stress, creating feelings of calm and physical wellness.

Pranayama 1

Try this practice when you’re feeling frustrated, stressed, or when you have low-grade anxiety.

1

Take some personal space in a safe environment.

Close the eyes.

2

Take a deep inhale, filling the lungs. Hold for a second or two. Exhale slowly in a relaxed way, taking longer than the inhale without creating tension.

3

Continue with this deep breathing rhythm for 1 to 5 minutes, or until calmness is restored.

Try to let go of the thoughts and internal story regarding whatever challenges or frustrations triggered the stress, and focus the mind purely on the breath for this short practice. Notice how you feel after the practice compared to how you felt at the start.

Pranayama 2

A committed practice; great to do at the start or end of every day.

1

Find a calm, safe space for your practice, free of disturbances. Take a comfortable seat, with a straight spine. Close the eyes. Relax the muscles of the legs, arms, and shoulders. Relax the jaw, muscles of the face, and eyes.

2

If you know ujjayi pranayama (gently constrict the glottis of the throat, making an ocean-sound) use this breath for the duration of the practice, otherwise continue with your natural, unobstructed breath.

3

Gradually, count the length of your natural exhale (usually around 3 or 4 counts). Then bring the inhale to match the length of the exhale.

4

After a few rounds of balanced breath, begin to extend the exhale, working toward a 1:2 ratio of inhale to exhale. For example, if you inhale to a count of three, try working toward exhaling to a count of 6.

5

Allow the breath and transition to feel easy in the body without creating additional tension; only extend the exhale as far as feels comfortable. Continue watching the breath with the exhale longer than the inhale for as long as comfortable. Allow thoughts to arise and pass away as your focus stays steady, witnessing and counting the breath.

6

After 3 – 10 minutes, drop the counting and witness your natural breath. Notice the stillness between the inhales and exhales.

To close and strengthen the effects of the practice, call to mind whatever you naturally feel grateful for today. Allow the feeling of gratitude to resonate through the heart. Close with sounding aum, a prayer, a mantra, or the intention of extending these feelings of peace to all beings.

The Body, Breath, Mind Connection

In this way, when we practice pranayama and mindful breathing practices, we are bringing our awareness into typically unconscious processes in the body and guiding them into balance.

Similarly, through regular mindfulness practices, we can halt the automatic, unconscious stress and fear-responses and cultivate more relaxation and calm presence, affecting changes on our mental states and thought patterns as well as having direct cascading physical benefits throughout the body.

Using the breath as a tool, we can guide our minds and bodies into greater health, wellness, and peace.

So much gratitude to author Rick Hanson for compiling and summarizing a plethora of neuro-physiological research behind mindfulness practices for the common practitioner. For more scientific detail or specific studies, please check out his book Buddha’s Brain.