Genesis of a Buddha Part 2: The “Ancient Path” as Taught by Gautama

Seated under a bodhi tree on a full moon night, Siddhartha made the firm resolve that he would remain there, motionless in meditation, until he would break through the final frontiers of the mind and enter a state of consciousness permanently free from all suffering – Nirvana.

After many hours of progressively deeper meditative absorptions, and many inner trials & tribulations, the penultimate experience of human life dawned within his mind and he emerged out through the other side as Gautama the Sama Sam Buddha – the perfectly awakened one.

Having merged his own consciousness into the very fabric of existence and then transcended the entire field of mind and matter, the unimaginable experience of omniscience, omnipresence, and omnipotence became Gautama’s own.

He remained absorbed in nirvana for the next 49 days, with only brief periods of deep reflection upon his experience in which he codified his revelation as the famous 4 Noble Truths and 8-Fold Noble Path, as well as the lesser known 12-Fold Law of Dependent Origination and the 4 Establishments of Mindfulness; which would all culminate to eventually form the core of his teachings.

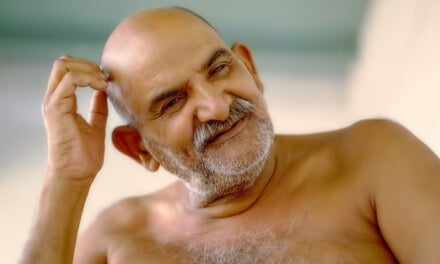

Buddha’s Enlightenment

Yet, contrary to popular belief, what the Buddha realized during his enlightenment was not a new or unique discovery, nor, surprisingly, were the methods he utilized to enter nirvana, called shamata (awareness of the natural breath) and vipashyana (insight meditation).

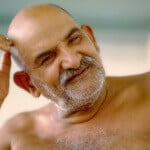

As the well respected and revered modern day vipashyana teacher S.N. Goenka, once said:

“In his last life, as Siddhartha Gautama, with darkness all around, words highly praising vipashyana still existed in the Rig Veda, but were mere recitations. The practice was lost. Due to his past paramis (good karmas) he went to the depth and discovered it…he called it purana marga, an ancient path. He discovered and distributed a dormant, forgotten path.”

– S.N. Goenka (Mahasatipatthana Sutta Discourses)

Thus, the teachings and the methods to enlightenment that Gautama shared were simply a rediscovery of what the Rishis of the Rig Veda had already revealed.

Was Buddha a Buddhist?

Modern Vedic scholars claim that approximately 94% of the Vedas have been lost to mankind. They make this declaration based on accounts in the Vedas themselves that reference certain sets of mantras that are said to exist, but are currently no longer available. They have been lost in time, as the breakdown in the oral tradition took place over the centuries.

Given the sheer antiquity of the Vedas, which likely date past 10,000 B.C.E., it is not hard to imagine that even at the time of birth of the Buddha (624 B.C.E.) much of the Vedic knowledge would have already been lost.

The implications of this understanding are enormous because contrary to popular belief, Buddha did not teach a new religion.

In fact, like all great teachers, the message of the awakened ones is universal – never sectarian or partisan. Buddha was not a Buddhist in the same way that Christ was not a Christian, nor were the Rishis Hindu.

Gautama had no intention to start a new religion, nor have his teachings become an “ism.” This is something that happened at a much later time, hundreds of years after his death, which he would not have likely condoned.

The Buddha did not teach Buddhism. He taught Dharma – the Sanatana Dharma, the eternal truth.

Key Similarities and Differences

If one examines his life and teachings closely, one will not find any trace of antagonism between his liberation teachings and what came before him.

There were obvious places of difference between what Gautama Buddha taught and what was in vogue at that time, but nowhere in his teachings did he refute the Vedas. He was simply not satisfied with the Vedic rituals and yogic techniques available to him; as he realized that though they promised ultimate liberation, they afforded him none.

If anything, we can see that Buddha was deeply steeped in the Vedas. He was born in a Vedic family of the bloodline of Gautama Maharshi one of the original sapta rishis, the 7 great sages of the Vedas (from which his own name was derived). He was initiated into the Gayatri mantra, which is the vibrational essence of the Vedas. He wore the sacred thread, a Vedic tradition, until his renunciation of the material life, and he learnt yogic techniques from the hermits of North India.

Though it is true that what he learnt from the yogis Alara Kalama and Uddaka did not satisfy him, this initial yogic training impelled him to look even deeper within to discover the hidden truths of the Rig Veda.

Whereas he had no interest in Vedic rites and rituals, even after his subsequent enlightenment Gautama would often give commentary on verses from the Vedas to help clarify obscure points. One such example was when he taught the famous Brahmin Uruvela Kassapa, which the contemporary Buddhist teacher, Thich Nhat Hanh has portrayed through this anecdote:

“Kassapa marvelled at how deeply versed the Buddha was in the Vedas. He was further astounded to discover that this young monk had grasped certain concepts in the Vedas which had eluded his own understanding. The Buddha helped explain certain of the most profound passages in the Atharva Veda and Rig Veda scriptures which Kassapa thought he had understood but discovered he had not yet truly grasped. Even more amazing was the young monk’s knowledge of history, doctrine, and brahmanic rituals.”

– Thich Nhat Hanh (pg. 255 Old Path, White Clouds)

Furthermore, if one studies and practices the essential teachings of Gautama, one will see that few real deviations from Vedic teachings occur.

Buddha taught that living a life of morality is the cornerstone of spiritual life. In fact, four of his moral precepts are identical to Patanjali’s ethical disciplines (in Buddha’s teachings aparigraha, non-covetousness, is replaced by abstinence from intoxicants).

He taught the law of karma, was a vegetarian, believed in rebirth and used many linguistic terms like samsara and nirvana, which have their origin in the Vedas, to describe his own experiences.

In fact, shortly after his enlightenment, and in subsequent times throughout his life, he had visions of Brahma – the patron deity of Vedanta, as well as various other Vedic deities, like Indra and Mara.

While it is true that Buddha refrained from commenting on key Vedic concepts like Brahman (the Absolute) and Ishwara (God), this need not necessarily mean he was either atheist or agnostic. He likely chose to divert philosophical discussions away from the speculative to the practical tasks of morality, mental mastery and the cultivation of wisdom.

Yet, if we compare the position of other Vedic sages, Buddha was definitely not alone when he chose to remain silent on the issue of God. Take for instance Kapila Maharshi, who also posits no Ishwara in his Samkhya Darshana – one of the defining philosophies of the Vedas.

Some say that the key concept of the permanence of the Atma (soul) was vehemently rebuked by the Buddha, which it certainly was, but differences in key conceptual understandings between enlightened sages is not uncommon, and is not ample enough ground to state that Buddha’s teachings were explicitly revoking the Vedas.

This subtle conceptual discrepancy is more a matter of disagreement with the commonly held Vedic belief, rather than a full rebuttal in which he chose to abandon the Vedas and forge his own new religion.

Furthermore, in the ancient Pali Abhidharma texts that contain the teachings Gautama gave in his sermons, it is clearly stated that the higher knowledge that he taught consisted of five categories:

1.

Veda Vidya – the knowledge of the Vedas

2.

Mantra Vidya – the knowledge of incantations

3.

Gandharva Vidya – the knowledge of supernormal powers

4.

Lokhya Vidya – the knowledge of psychic feats

5.

Arya Vidya – the knowledge of the 4 Noble Truths

Why All The Confusion?

If all this is true, then why all the confusion regarding Buddha’s Vedic teachings?

Why do so many frequently position the Buddha as having taught something so contrary to the spirit of the Vedas?

The answer is complex and multi-faceted. It requires a deep understanding of India’s rich cultural history, linguistics, the protocols of philosophical debate, yogic techniques, sociology, human nature and psychology, amongst other factors.

Due to the sheer complexity of untangling the knots of confusion that have set in on a global scale regarding this issue, I make no presumption that this misunderstanding will be illuminated anytime soon.

Understanding the Buddha’s Vedic Teachings

However, one of the key nuances of the Buddha’s teachings is that as a sanyasi (renunciate), he focused his life and teachings only on the fourth part of each Veda – the jnana khanda (the wisdom teachings).

Buddha was fundamentally a jnana yogi, and as such, had no need nor use of the first three parts of the Vedas, which deal with the chanting of mantras, rituals and yogic techniques to purify the mind – the karma khana (the teachings on right action)

As such, he was specifically disinterested in rites and rituals as a means to realize nirvana – for this is not their objective.

The Buddha was a masterful teacher and focused only on the highest truth of the Vedas, which he experienced directly, and expressed his experience through a unique language all his own – a language that emphasized the most subtle and abstract concepts in the Vedas that few could truly comprehend without practicing deep meditation.

He often gave great emphasis to the principles of impermanence, the origin, cause & path out of suffering, as well as the interdependence of all phenomena. Such subject matters were rarely addressed in the Vedas, due to their exceedingly subtle and elusive nature. These are universal principles that only a highly refined and pure intellect can comprehend.

It was only during his enlightenment that Buddha rediscovered the ancient technique of vipashyana which has the power to illuminate these three core universal laws and develop full insight into their true nature; so as to permanently liberate the mind from the sorrows of conditioned existence.

This Vedic meditation methodology is at the core of Buddha’s practical teachings. Though it is currently known by its Pali name vipashyana, in the Vedas this technique was known as vidarshana, which roughly translates as insight or a clear view of reality.

The Rig Veda technique of vidarshana as rediscovered by Gautama the Buddha, comes from the Vedic Rishis – who themselves claim no ownership over it. It is as old as the Vedas themselves. As Buddha himself once said:

I have “seen an ancient way, followed an ancient path.”

– Gautama Buddha